In Part I of this series, I mentioned how South Korea, China, and Russia view some of the most powerful people and moments in their history. It is interesting to see how South Korea memorializes their history in a light that tends to make sense. Seemingly calling a spade a spade. For China and Russia, however, in regard to Mao and Lenin, the memories seem skewed, if not perverted to the extent to make them out to be great men who had not ushered in the violent and unnecessary deaths of scores of millions.

In this light and in light of the domestic terror act in Charlottesville on Aug. 12, we need to consider precisely how we are looking at our monuments and memorials. There are currently more than 700 Confederate statues in the nation.

WHAT DO THESE STATUES REPRESENT?

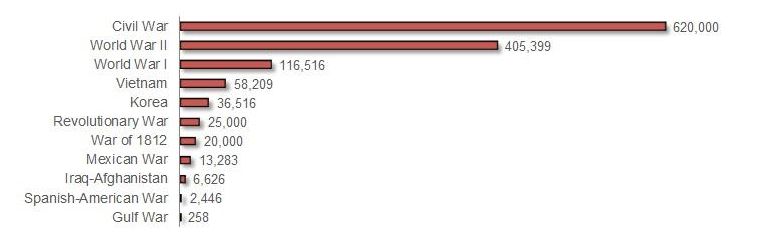

The question is why do these statues still remain in parks, cities, and town squares? The Confederacy invokes the memory of this country’s darkest hour, where more Americans were killed than in any other war. According to the Civil War Trust, we lost 620,000, which was 200,000 more than World War II.

There are those who rightly indicate that the South fought because of the ever-increasing encroachment on states rights and the North fought because the South had broken up the United States. But to contend states rights and unification were the sole reasons for the war is to suggest that history itself suffers from amnesia. We know and are very aware of the scourge that was slavery in this country and an attempt to nullify this fact would be a dereliction of the sacrifices made on both sides—those who fought against it and those who fought to retain it.

For the sake of arguing with those who know American history best, as well as those who pretend to know American history best, the Civil War began with ending slavery as a secondary consideration, yet ended as one of its primary outcomes. In fact, the Union’s intention was to merely stop the expansion of slavery; it was only later that its abolishment was advocated. The Confederacy had no intention of stopping its expansion, much less the abolition of it.

WHY DO THESE STATUES REMAIN?

Therefore, when the Civil War is mentioned, the first thought that comes to mind is American slavery. Whether that reaction is historically accurate in a numerically hierarchical sense is irrelevant.

What is relevant is the purpose of displayed relics, whether they are Confederate solider statues or the Rebel flag. These are symbols of America’s past, but the darkest part of our past. So when the darkest part of our past is placed on display in parks, cities, and town squares, the question is why? What is their purpose? Are they for education? Are they to honor the fallen soldiers who tried desperately to destroy the Union? Are they to shame them? Whether the purpose behind these publicly displayed symbols is multi-pronged or not, their historical provocation is singular: slavery.

I must disagree with those on the left who suggest that those who honor the Rebel flag or fight for Confederate statues are white supremacists or racists. In much the same way, I disagree with those on the right who suggest that these symbols are not representative of slavery.

WHAT SHOULD WE DO WITH THESE STATUES?

Some of these statues are over a century old. These are more than symbols of American history; these are, as I stated before, relics. I believe these symbols are the signs of struggle within our country that should be rightly constructed, not haphazardly placed. Of the 620,000 sacrifices made on both sides, I do not believe we do any of them justice by placing Confederate statues on a pedestal as if claiming that there was no wrong side. To place them in parks, cities, and town squares suggests one of two ideas: that the Confederate cause was just or that the Union cause was suspect.

Destroying these statues, however, does nothing but cause civil unrest; although it appears there are a number of Americans who are preferential to unrest. Keep in mind that a vast majority of the Confederate soldiers were not slaveholders. A majority of those whose images were made into statues, however, were. Regardless, a Confederate victory would have secured slavery for the foreseeable future.

If Confederate statues and Rebel flags are truly only a representative of a time we must remember yet wish had never happened, then place them where they can be perceived in that specific light. Forgetting the past dooms you to repeat it. Put them into museums. Place them on the Civil War battlefield memorials. Create Civil War parks that educate rather than simply placate. The future generations must know their past. Not ignore it or misconstrue it.

While the far left is hell-bent on the destruction of the present and the far right is hell-bent on glossing over our destructive past, we must be precise in our future. The future is and has always been the continual struggle for unification, to remain unified, and to “form a more perfect union.”

Misrepresenting these symbols as well as destroying them does an extreme disservice to our past, our present and our future. Just as South Korea’s war, China’s Mao and Russia’s Lenin should not be forgotten, neither should those who fought for the Confederacy. It merely comes down to if we are remembering them accurately.

As we deal with this struggle to eliminate confusion and strife amongst our fellow man, I think it best to end with the final words of President Abraham Lincoln during his second inaugural address:

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

P.S. – I encourage you to read all of his March 4, 1865 inaugural address.