Last year I visited South Korea. It is a country of rich history. And, since 1945, a divided and divisive history.

Before flying from Houston to Beijing to Seoul, I had spent more than two years studying the Korean War, Korea, and the general outskirts of East Asian culture (i.e. Korea, China, and Japan). I learned that Korea had been a far more often than not peaceful country with very few conflicts from its northern neighbor, China, and southern neighbor, Japan. The peninsula had two primary dynasties, Koryo and Joseon, both lasting approximately 500 years each. That timeframe is comparative to the great dynasties of China.

A BRIEF HISTORICAL REVIEW OF KOREA

Stemming from Chinese descent more than 3000 years ago, Korea broke into three regions, where infighting took place to unify in 668, extending its region to the north around 250 years later, and then the rise of two great dynasties. The dynasties cover about 1000 years before the rise of globalization, which it fought as best it could until being forced open by the powers of Japan, America, Russia, and Britain. It lost its independence rather rapidly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, eventually becoming a colony of Japan. Then the arrival of World War II brought a Japanese surrender, and the country was split haphazardly in half by the Americans and Soviets. One half belonging to Communism and the other half belonging to Democracy. We now know where North and South Korea stand today—on very different levels.

THE NECESSITY OF HISTORICAL MEMORIALS

Upon my visit, I visited Seoul, Incheon, Busan, and the DMZ. I walked through the many palaces and temples. I toured the Times Square-like downtown of Seoul. I noticed the Americanization of South Korea. I photographed the many statues dedicated to its heroes, like Sejong the Great and Yi Sun Shin. I also took photos of the small Comfort Woman statue next to the Japanese Embassy that serves as a reminder of what the Japanese did to the Korean women and girls during World War II. I also took a long visit inside the War Memorial of Korea, which has an incredible memorial to the Korean War.

All of these historical fixtures—palaces, temples, and statues—serve as a reminder of a great heritage and a painful past. The skyscrapers, the well-manicured Gwanghawmun Square, and the booming economy are declarations of how far the country has come since the days of the Korean War. The dates, June 25, 1950 or July 27, 1953 are visible almost everywhere in South Korea as reminders of the start and end dates of the war.

These memorials are important to the culture of South Korea and its current and incoming generations. Knowing the past of one’s country doesn’t necessarily equate understanding one’s country. History repeats itself when a people disregard its past.

PREPARED BY MEMORY

One of the most powerful photos I took while in South Korea was at the War Memorial of Korea where I saw several small boys, who were possibly no older than four or five. They stood beside a tank, saluting and pointing finger guns at their teacher’s camera. It was a very intriguing moment because it summed up the feeling the South Koreans have toward their greatest threat: North Korea. This feeling is not of hate, but of readiness. Having experienced a war that cost more than 2 million Korean lives, followed by skirmishes, assassinations, kidnappings, and the ever-present nuclear threat, the South Koreans hold to their relics, their monuments, and their memorials, not for the sake of knowing about their past, but for the sake understanding it. The power of understanding their past is the best chance the country has to continue to not merely survive, but thrive.

THE MEMORIES NOT TO BE GLORIFIED

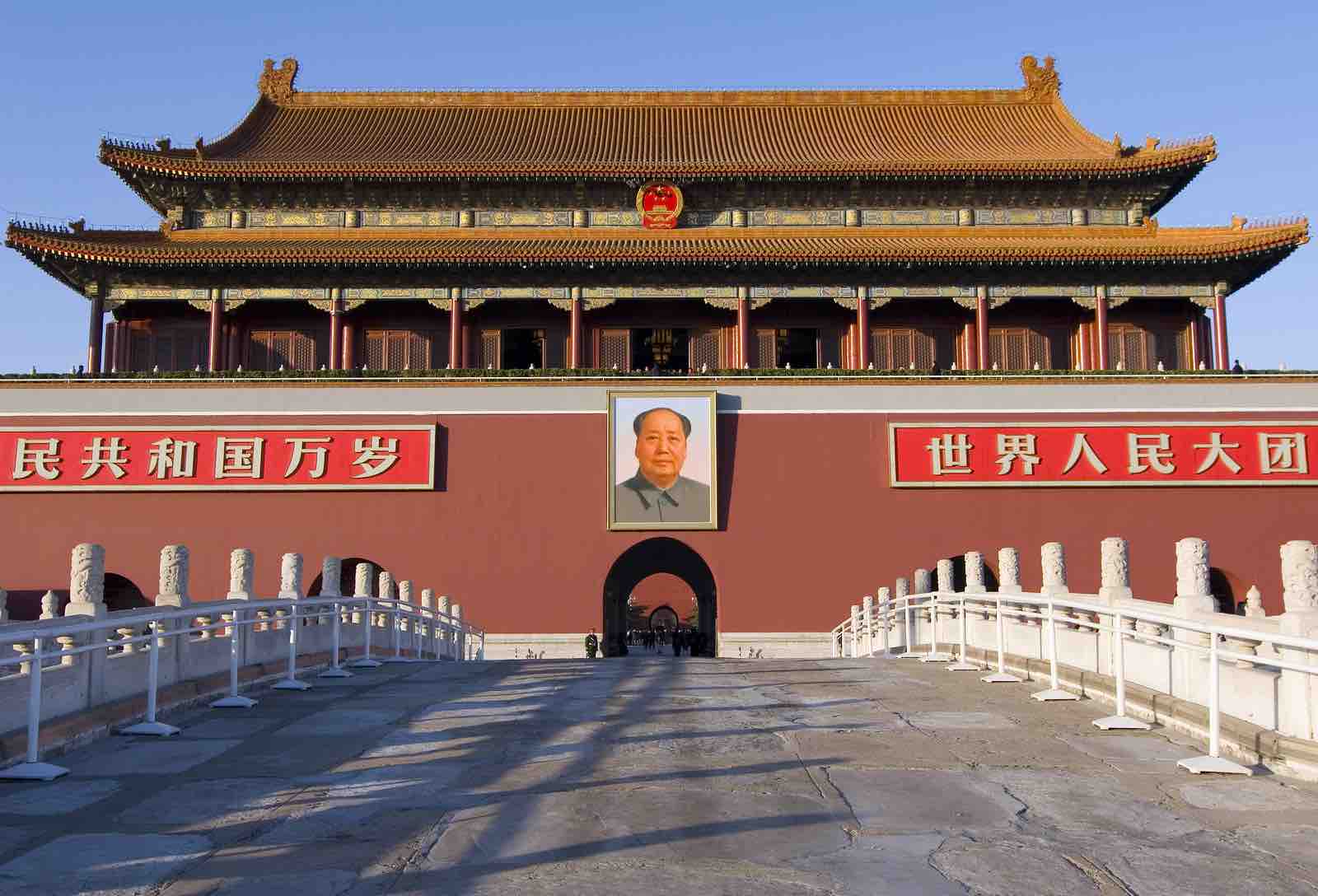

Not very far away (in a relative sense) from Seoul is Beijing, which is home to Tiananmen Square. Overlooking the Square is the large picture of Mao Zedong, the Communist dictator who reigned over China for 25 years. His regime, through subjugation (the Cultural Revolution) and economic planning systems (the Great Leap Forward), cost the lives of approximately 100 million people (read Mao:The Unknown Story)—primarily due to starvation. His authoritarian control ensured the absence of civil liberties. Since his death, China has instituted capitalism, but the use of Communism is still prevalent.

The Mao reign was a time of bloodshed and extreme civil restrictions, yet his picture remains proudly placed in one of the most prominent areas of the capital city. For some, it is a reminder of brutality and captivity. To others, it is the symbol of stability and independence. History has proven the former to be more accurate.

In Russia there are various statues of Vladimir Lenin throughout the country. Lenin is known for bringing Communism to Russia through the Bolshevik Revolution (this year marks the 100-year anniversary). His rule kept freedom from the Russian people, which was something they didn’t have under the Czars either. In much the same way, his methods caused the deaths of millions, and when he selected Stalin to take over in his stead (read Stephen Kotkin’s Stalin), it is argued that around 50 million more died from starvation, forced labor, and the Gulag (you can read more about that in this post).

The question is why are these statues still around? They are not propped to educate citizens of their brutal past and warn the future generations away from it. No, these Mao and Lenin memorials remain to honor the two former leaders. In a sense, to romanticize their cruelty and devastation (sort of how The New York Times continues to do in their Red Century series).

THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN MEMORIALS

As I stated above, knowing the past of one’s country doesn’t necessarily equate understanding one’s country. History repeats itself when a people disregard its past.

Here we have three separate countries—South Korea, China, and Russia—that utilize memorials in very different ways. The question now comes to us as Americans in reflection of the domestic terror act in Charlottesville. This is not a new conversation, yet the tone has taken a different pitch. Part II of this series will discuss exactly what should be done with our memorials and how we should perceive them.