One hundred and five years after his conviction, Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion of the world, finally received his pardon on May 24. President Donald Trump signed the pardon for the larger-than-life character with several larger-than-life characters around him: Sylvester Stallone, Lennox Lewis, and Deontay Wilder.

Born in Galveston just 14 years after the end of the Civil War, Johnson was a man loved and hated for the most obvious of reasons—his greatness and his blackness. Imprisoned for violating the Mann Act (instituted June 1, 1910), which had been created to stop the trafficking of women “for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purposes.” The loose language of the bill seemed to cover broad arrangements like sexual relations between consenting adults. Not to go into detail about the whole ordeal, but Johnson was soon unjustly accused and charged. He lived in exile for seven years before finally returning home to the States to serve his sentence.

Before he was accused and served time, Johnson was the greatest boxer and was never intimidated by anyone—black or white, in or out of the ring. When I read his biography, Unforgiveable Blackness, by Geoffrey C. Ward, (which Ken Burns turned into a documentary) I realized how bold and fearless this man was. Built like a god, he brutalized other boxers, and far more often than not, at his leisure.

It was during the Jack Johnson reign that the term “Great White Hope” originated. When Johnson finally got his chance to fight for the championship on Dec. 26, 1908 against Tommy Burns, he didn’t disappoint. He knocked Burns down within seconds of the first bell and then punished him for 14 rounds. Burns had made Johnson chase him practically around the globe for two years, always denying Johnson a shot at the title (much like many others had), and for that he made him pay.

“I could have put him away quicker, but I wanted to punish him,” Johnson said of Tommy Burns. “I had my revenge.”

Johnson didn’t just break the color barrier in boxing, he knocked its block off, as expressed in the New York newspaper, the Morning Telegraph, calling Johnson the “Champion face smasher in the world.” The paper went on to say that “the color line question is receiving an unusual amount of public attention. The color line was…used in the most select pugilistic circles of subterfuge behind which a white man could hide to keep some husky colored gentleman from knocking his block off and wiping up the canvas floor of a square circle with his remains.”

Johnson’s win, which for all intents and purposes was a necessity for black people, paved the way for future black fighters, and really the future of boxing. It eliminated the myth of the color line, a myth, as suggested in the Morning Telegraph, no one, black or white, really believed.

There is so much to Johnson’s story other than boxing and serving an unjust sentence. It is everything before, between, and after that time. It really isn’t a story of struggle as much it is of defiance. He lived fast and pretty wild, which often defined his defiant spirit outside of the ring. He was a towering figure for more than just being a heavyweight champion boxer and the first for his race. He demanded and commanded respect, and for the most part, received it. The downfall was the criminal charge that led to death threats, mass hatred, exile, prison sentence, and even Booker T. Washington officially disowning him. That conviction followed him for more than a century later.

To say that this pardon was long overdue is an absolute understatement. I’m just happy one of the presidents finally took up the issue and resolved it.

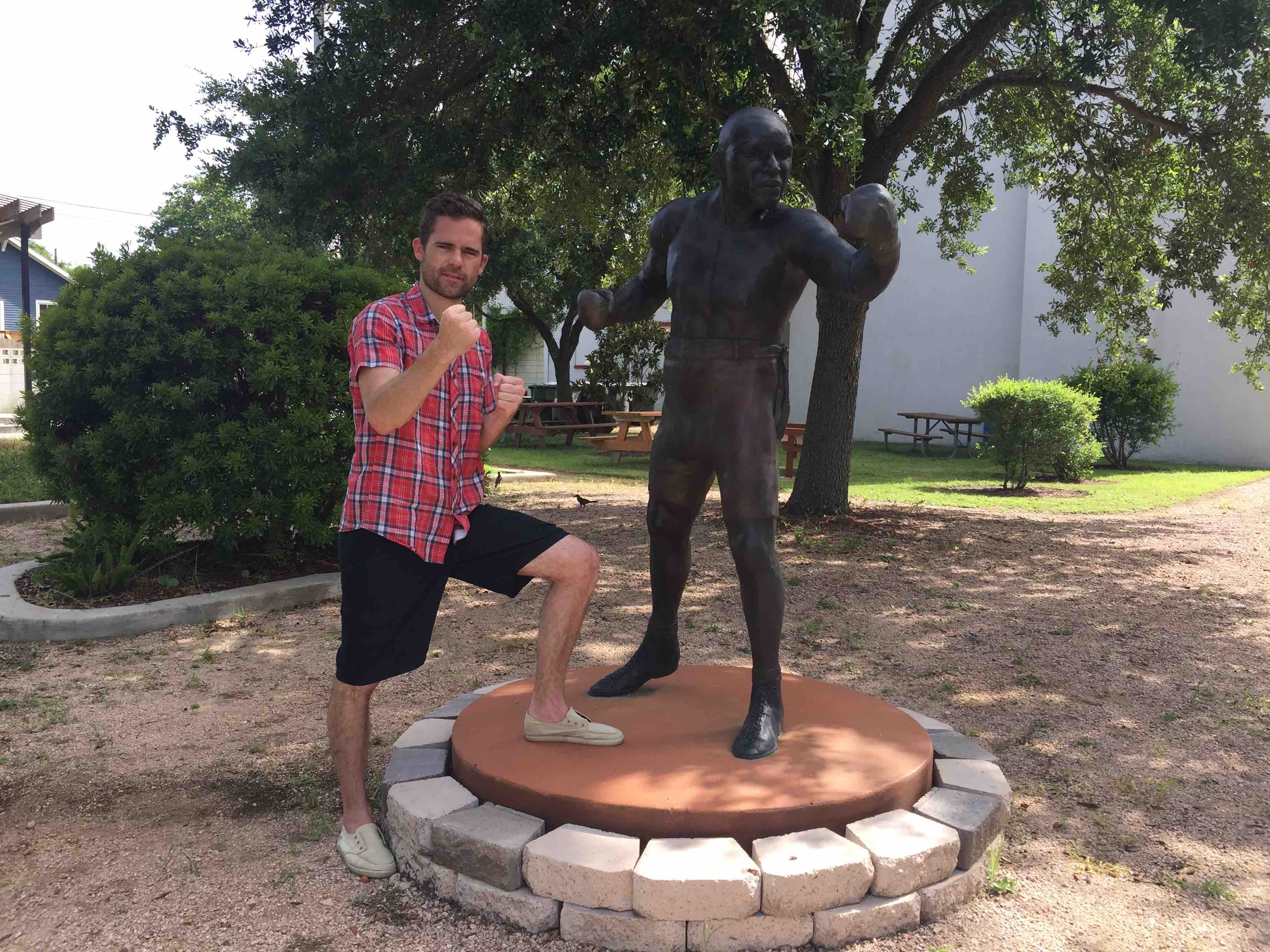

There is a statue of Jack Johnson in Galveston. Last summer I went to go see it. I can’t express how disappointed I was at the statue and its placement. It nearly brought me to tears. For a man who lived his life big, bold, and out in the open, to have his commemorative statue so small and tucked behind the Old Central Cultural Center doesn’t fit him or his historical significance. With a hint of irony, the statue itself, erected in 2012, took almost as long as the pardon.

He is one of the most important black figures—from a sports and social perspective—if not Texas, then most definitely Galveston, yet he is hardly known. As Jack Johnson once said, “There ain’t gonna be but one Jack Johnson.” We would be wise to remember that.

I personally believe the statue should be moved to a more prominent space, perhaps on the seawall or in the middle of Galveston’s The Strand. Too many people have no idea who Jack Johnson was and placing him in a quiet corner where nary soul ventures doesn’t do him justice. Maybe this pardon will get him moved to a more prominent location.

Regardless of where the statue ends up, however, I am just happy Jack Johnson finally got his pardon. It was a good day for boxing.